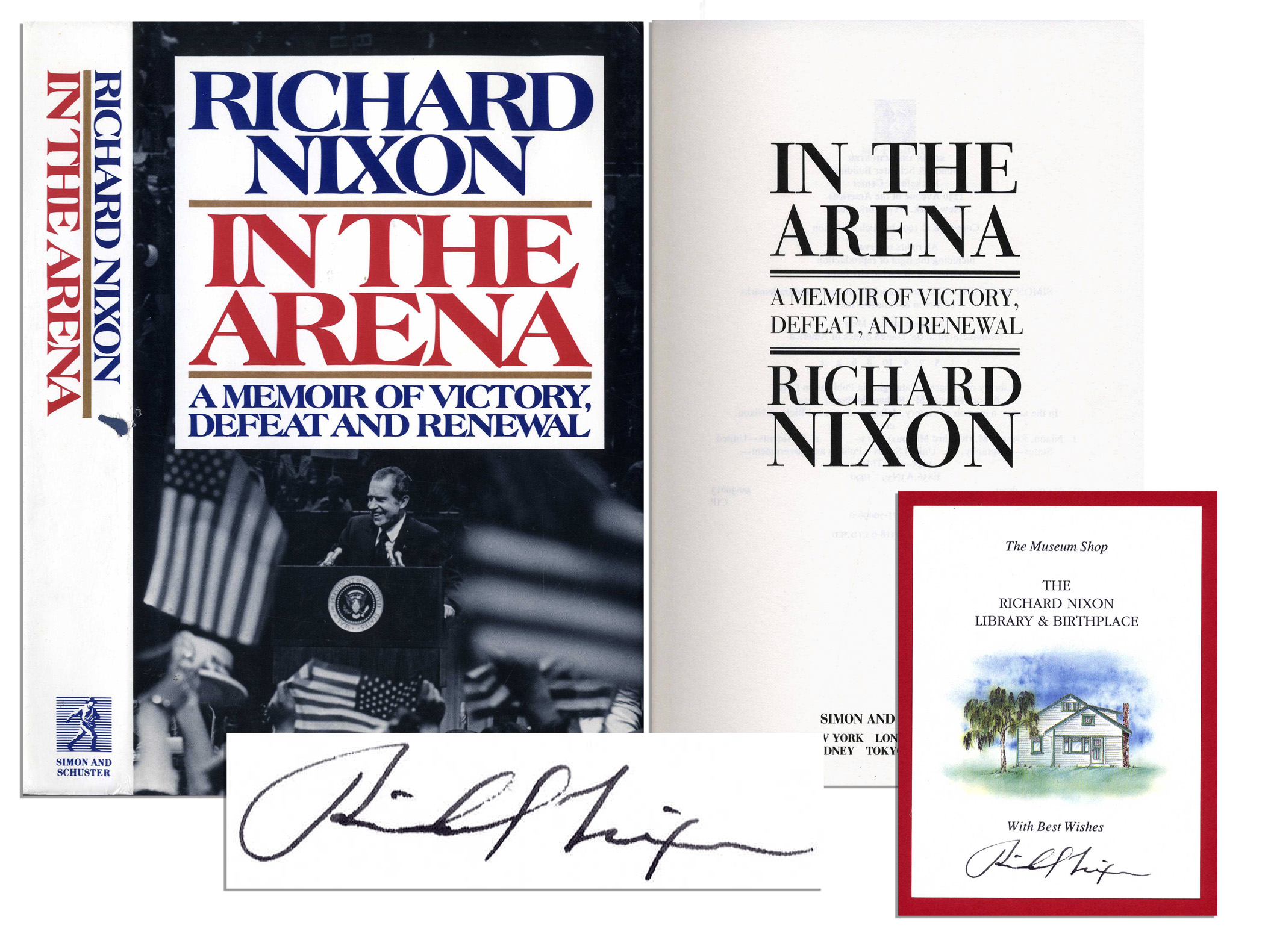

This book chronicles Richard Nixon's rise and fall with candid honesty and demonstarates a warmth and human falibilty that does indeed afirm Young's lyric. I was surprised at Mr. Nixon's book in that I was unsympathetic at the time with his handling of Vietnam and felt he was out of touch with the vast anti-war movement in the USA. Written following Nixon's loss to John F. Kennedy in the 1960 United States presidential election, this memoir includes the six major professional crises of Nixon's life to that point, including—in addition to the campaign against Kennedy—the Alger Hiss trial, the Checkers speech, and the. The former president recounts his life and political rises and falls, concentrating on the events, domestic and international, of his presidency and those leading up to his unprecedented resignation. This limited edition two volume set was published by the Richard Nixon Foundation to. Richard Nixon’s Memoirs, published in 1978, is an articulate, highly readable work. His later book, In the Arena, published in 1990, is a worthwhile follow-up along with Bruce Herschensohn’s superb analysis of the power of media influence titled The Gods of the Antenna, published in 1976.

April 24, 1994

OBITUARYThe 37th President; In Three Decades

By JOHN HERBERS

To millions of Americans, Richard Milhous Nixon was the most puzzling and fascinating politician of his time. He was a man of high intelligence and innovative concepts whose talents, especially in international affairs, were widely respected by both friend and foe. Yet he was so motivated by hatreds and fears that he abused his powers and resorted to lies and cover-ups.

Almost constantly in the public eye from the time he entered politics in 1946, he propelled himself into a career that culminated a generation later when he became the first President to travel to Communist China and the first to resign from office. Over the decades, he evoked conflicting emotions among millions of Americans.

Many felt an intense dislike for him on the ground that he rose to power through what they regarded as demagoguery and defamation of his opponents. But among many others he inspired an intense loyalty, particularly among those who identified with his humble beginnings and with his hostility toward intellectuals, liberals, socialists and others he regarded as archenemies.

Mr. Nixon wore his hatreds on his sleeve, and some of the most revealing information about his character and motivations came from his friends and associates. 'Richard Nixon went up the walls of life with his claws,' said Bryce Harlow, one of his Presidential aides.

His career, driven by such tenacity, was a tumultuous roller-coaster ride of victory, crisis, defeat, revival, triumph, ruin and, in later life, re-emergence as an elder statesman of the world who traveled widely, wrote copiously and offered advice freely.

'No one,' he told an interviewer in 1990, 'had ever been so high and fallen so low.'

Mr. Nixon's political life spanned the cold war. He began in politics as an ardent anti-Communist, and he spent his last years crusading for American political support and financial aid to Boris N. Yeltsin's Russia.

A Resignation, Not a Confession

Mr. Nixon never received the honors and accolades he would have earned had he not resigned the Presidency in the face of certain impeachment for the cover-up of a cheap political burglary of Democratic offices in the Watergate complex and other illegal acts of domestic espionage, all documented by Oval Office tape recordings.

Still, he never confessed to the 'high crimes and misdemeanors' of which he was accused in articles of impeachment, which were approved by the House Judiciary Committee and which precipitated his resignation in 1974.

'When the President does it, that means it is not illegal,' he told David Frost in a celebrated television interview three years after he was pardoned by his successor, Gerald R. Ford.

So strong was the stigma of the Watergate scandals that it tended to obscure Mr. Nixon's accomplishments. In foreign affairs these included establishing relations with Communist China, initiating detente and nuclear arms control treaties with the Soviet Union, and opening the way for Egypt to break with the Soviet bloc (and subsequently to make peace with Israel).

In the domestic arena, his record appears better through the prism of subsequent events, some scholars say, than it did at the time. In his Administration, an expansion of the food stamp program went a long way toward stamping out hunger in America. The Environmental Protection Act authorized vast resources and regulations for cleaning the country's air, land and water.

In fact, many of the Government regulations and expenditures for social programs that Ronald Reagan cut when he became President in 1981 were the products of the Nixon Administration rather than of the Democratic Presidents Mr. Reagan blamed.

Perhaps more important was Mr. Nixon's reshaping of the Supreme Court through his appointment of a Chief Justice and three Associate Justices. He appointed candidates for their ideological persuasion, particularly on such issues as judicial restraint, tough law enforcement and relaxation of school desegregation rules. As a result, the nine-member Court was transformed from the 'liberal Warren Court' to a body that was often split on the great issues of the day but more attuned to conservative causes.

Richard Nixon Memoir

A Push for Peace, A Bungled Burglary

Yet his accomplishments were marred to some extent by his methods, his motives and his ambiguities. Carrying out the 'peace with honor' agreement to end the long divisive war in Southeast Asia took five years from the time he was elected to office on a peace pledge, years in which American society was scarred by riots and rebellions against the efforts to force peace through bombings and incursions into new territory.

By the end of 1968, 30,610 Americans and untold Vietnamese had died in the war; over the next five years another 27,557 Americans and even more Vietnamese died. The men who negotiated the peace, Henry A. Kissinger and Le Duc Tho, were selected for the Nobel Peace Prize; Mr. Tho declined.

In all matters Mr. Nixon centralized power in himself and a few aides in the White House and sought to broaden the authority of the executive branch at the expense of Congress and the courts. He tried to use the bureaucracy against political foes. He entered his second term by interpreting his crushing defeat of George McGovern as a mandate to scale back domestic government, even though some of the programs involved grew out of the first Nixon term. But that effort was barely under way early in 1973 when the Watergate disclosures weakened him.

Watergate in its broadest sense -- not only the burglary of Democratic headquarters and subsequent effortsat a cover-up, but also the corruption of Federal agencies for illegal purposes -- had such an impact on politics and government that it remains a promontory on the landscape of American history.

In Watergate's wake Congress passed a proliferation of legislation intended to restore ethics to elections and government, to make government more open to the public, and to restrain agencies from abusing individual rights at home and abroad.

Citizens seemed to be so offended by Watergate that for several years they voted heavily against candidates of Mr. Nixon's party whether or not they had anything to do with the scandals. A result, Democrats swept Congress in 1974 and Jimmy Carter was elected President in 1976. The contest between Mr. Carter and President Ford was so close that many students of politics believed Mr. Ford would have won had he not pardoned Mr. Nixon, an act that prevented the kind of criminal prosecution that sent many Nixon aides to prison.

It was Mr. Nixon's personality and character that most caught the attention of Americans as, always accompanied by controversy, he went from Southern California to the House of Representatives, to the Senate, to the White House as Dwight D. Eisenhower's Vice President, to the Presidency, and to private citizen as the first President to have resigned the office. In years between, he was defeated in a race for the Presidency by John F. Kennedy in 1960 and, two years later, in a bid for Governor of California by Edmund G. (Pat) Brown.

No public figure had been more observed, discussed and psychoanalyzed in public, yet few professed to understand him.

'Though he was a remote and private man, we had all been drawn into his life story,' Garry Wills, author of 'Nixon Agonistes,' wrote after the resignation. 'Decade by decade, crisis by crisis, we were unwilling intruders on his most intimate moments -- we saw him cry, sweat, tremble, saw him angry, hurt, vindictive. The tapes even let us eavesdrop on those embarrassing conversations. Although no one really knew him, we all knew too much about him. He was too vividly present, and yet not present at all -- a collection of quirks, and not a person; a conspicuous absence.'

On another level, there were those who asserted that the apparent Nixon enigma stemmed not from his character but from his fruitless efforts as President to persuade the people to take a more pragmatic view of government, particularly in foreign affairs, a view that neither the right nor left was quite prepared to adopt.

Calling the Nixon era 'a golden age of diplomacy,' William Tucker, a writer and magazine editor, wrote in 1981: 'The Nixon approach was always hated by the far left and far right -- groups that despite doctrinal differences see the world in terms of absolute right and wrong. The right hated Nixon because he had abandoned the anti-Communist cause; the left was unforgiving of the former Richard Nixon, and resentful because he turned out to be such a constructive diplomat. Watergate had little to do with it.'

Americans did not know who Richard Nixon was in part because he had no fixed ideology, no particular place on the political spectrum. He was a loner who had no lasting alliances with other prominent Republican leaders. At one time or another he was at cross-purposes with Dwight Eisenhower, Barry Goldwater, Nelson Rockefeller, Ronald Reagan, Earl Warren and others.

His life was a series of contradictions. He preached the Protestant ethic of hard work and moral living and was prim in dress and manner. Yet the White House tapes that came to light in the Watergate investigation, as well as the testimony of some of his associates, showed that he could be profane, amoral and power-driven.

A Faith of Peace, A Policy of Force

Reared as a Quaker, Mr. Nixon said he was strongly influenced by that faith of peace and contemplation. Yet he considered politics combat and election campaigns an 'arena.' A foundation of his foreign policy was to appear ready to use military force anywhere in the world.

Like Lincoln and Jackson, he identified with the common people, siding with 'middle America' against the well-to-do. But his own style of living was extravagant, with two expensive homes in California and Florida subsidized by wealthy friends and the Federal Government.

He entered the White House promising to decentralize authority but almost immediately consolidated it in himself and a few aides at the expense of his Cabinet.

He invited crises and, until the Watergate scandals closed in, thrived on them, but he felt depressed after a victory, as he wrote in his book 'Six Crises.'

He entered politics by falsely branding his opponent for a House seat as an ally of Communists and their sympathizers. Yet as President he opened relations with the Communist Government of China and established a rapport with Soviet and other Communist-bloc leaders that no previous President had achieved.

Some Nixon observers have sought to explain him as an early practitioner of 'the new politics,' in which the dominant ingredients are a weak party structure and the mass appeal of television.

California set the trend. There, Mr. Nixon was able to run for Congress without working his way up through party ranks, as was the custom in most other states in 1946.

Six years later, Mr. Nixon discovered in his celebrated 'Checkers' speech that on television he could move audiences without being subjected to questions and checking of his facts. Thereafter, he used television whenever he could and became a master of the controlled broadcast that conveyed the image he desired.

None of this, however, explains Richard Nixon. He was a man of enormous complexity. Many volumes have been written about him in an effort to penetrate his core. He himself provided the best clues.

'They'll Never Give Us Credit'

Kenneth W. Clawson was communications director for Mr. Nixon and a loyalist who stayed with him to the end. Shortly after Mr. Nixon resigned and returned to San Clemente, Calif., he sent for Mr. Clawson, who had grown up in Appalachia and admired the Nixon style and determination.

Mr. Clawson found 'the Old Man' depressed and nursing a bout of phlebitis, his legs propped on his desk.

'They'll never give us credit,' he said to Mr. Clawson, who wrote of the conversation in The Washington Post in 1979. 'Even now they try to stomp us, you know, kick us when we're down. They'll never let up, never, because we were the first threat to them in years. And, by God, we would have changed it all, changed it so they couldn't have changed it back in a hundred years, if only . . .'

There was no explanation of who 'they' were, and no need for one. They were the liberals, the intellectuals, journalists, those born to privilege, the anti-Nixon people in his own party, those Mr. Nixon had counted as his enemies over many years.

'What starts the process, really, are the laughs, slights and snubs when you are a kid,' Mr. Nixon said. 'Sometimes it's because you are poor, or Irish or Jewish or Catholic or ugly or simply that you are skinny. But if you are reasonably intelligent and if your anger is deep enough and strong enough, you learn you can change those attitudes by excellence, personal gut performance, while those who have anything are sitting on their fat butts.

'Once you learn that you've got to work harder than anybody else, it becomes a way of life as you move out of the alley and on your way. In your own mind you have nothing to lose, so you take plenty of chances, and if you do your homework many of them pay off. It is then you understand, for the first time, that you really have the advantage because your competitors can't risk what they have already. It's a piece of cake until you get to the top. You find you can't stop playing the game the way you've always played it because it is a part of you and you need it as much as an arm and a leg.'

Patting his swollen leg, he added: 'So you are lean and mean and resourceful, and you continue to walk on the edge of the precipice because over the years you have become fascinated by how close to the edge you can walk without losing your balance. This time there was a difference. This time we had something to lose.'

That short conversation provides a thread that ran through Mr. Nixon's entire life, a life lived on the precipice and, for the most part, sustained by skill, determination and a good bit of luck.

EARLY YEARS

Quaker Church, Football Field, Role in War, Taste of Politics The future President was born Jan. 9, 1913, in Yorba Linda, Calif., then a farming community of 200 people near Los Angeles. His ancestors on both sides were farmers, artisans and tradesmen who came to America from Ireland in the 18th century.

Francis Anthony Nixon, Richard's father, was born on a farm in Ohio, left home at the age of 14 to earn a living and arrived in California several years later, in 1907. He found a job as a trolley-car motorman in the Quaker community of Whittier, where he met Hannah Milhous, whose family had come there from Indiana in 1897. Frank and Hannah were married in 1908.

After working in his father-in-law's orchards and in several other jobs, Frank bought a general store and filling station in 1922. Richard was the second of five sons.

'It was not an easy life, but it was a good one,' Richard Nixon recalled in his memoirs, 'centered around a loving family and a small, tight-knit Quaker community.'

Childhood friends of Mr. Nixon's said he rarely smiled. In 'The Presidential Character,' published in 1972, James David Barber cited a 'lifelong propensity for feeling sad about himself, with his Duke Law School roommate's observation that 'he never expected anything good to happen to him, or to anyone else close to him, unless it was earned.' '

He daydreamed of faraway places; worked hard at winning good grades in school; lectured his brothers to be more conscientious; played football with zest even though he was not good at it; pursued music, acting and debating and competed for leadership positions in school, and went four times a week to a strict Quaker church.

He was close to death and illness at an early age. A younger brother, Arthur, died of tubercular encephalitis when Richard was 12. When Richard was 20, his older brother, Harold, died of tuberculosis after a 10-year illness that drained the family resources.

At the age of 3, Richard toppled from a horse-drawn buggy, and the wheel ran over his head, inflicting a deep gash in his scalp that left an ugly scar.

'Out of his childhood Nixon brought a persistent bent toward life as painful, difficult, and, perhaps as significant, uncertain,' Mr. Barber wrote.

Some students of his career concluded that as an adult, Mr. Nixon would make his investment in life not in values but in managing himself so he could accomplish his next goal. And in the process, he was not as enigmatic as he was often pictured. Rather, his behavior was consistent with his view of the world and was perhaps more predictable than that of most politicians.

After he had become famous and served as Vice President, his mother was asked if her son had changed over the years.

'No,' she replied. 'He has always been exactly the same. I never knew a person to change so little.'

The Upward Ladder: Fighting to Win

After graduation from high school, the young Nixon wanted to go to Harvard or Yale. But there was no money for that. So he stayed four more years in the community he wished desperately to escape and entered Whittier College. There he sharpened his debating talents, was elected president of the freshman class and of the student body for three years, and took acting lessons.

But it was his football coach, Wallace Newman, who influenced him the most. 'I admired him and learned more from him than any man I have ever known aside from my father,' Mr. Nixon said.

In his memoirs he said of Mr. Newman, 'He had no tolerance for the view that how you play the game counts more than whether you win or lose. He used to say, 'Show me a good loser and I'll show you a loser.' '

Graduating from Whittier second in his class, Mr. Nixon won a scholarship to the Duke University Law School in Durham, N.C. There, he was so short of spending money that he spent most of his time in study. He was elected president of the Duke Bar Association and graduated third in his class.

Mr. Nixon tried to get a job in one of the big New York law firms, particularly Sullivan & amp; Cromwell, but he received no encouragement. The Federal Bureau of Investigation also turned him down. He went back to California and was admitted to the bar in November 1937; he almost immediately joined the firm of Wingert & amp; Bewley in Whittier.

In his spare time, he became active in civic groups, taught Sunday school and acted in a little theater group. It was in the theater that he met Thelma Catherine Ryan, called Pat because she was born March 16, a day before St. Patrick's Day, in 1912. When they met, she was teaching typing and shorthand at Whittier High School. They were married two years later, June 21, 1940, in a Quaker ceremony.

When the United States entered World War II in 1941, Mr. Nixon took a job in Washington as a lawyer with the Office of Price Administration, an experience he loathed and would cite in later years as evidence of the failure of government bureaucracy. After seven months he applied for and was granted a Navy commission. He became an operations officer with the South Pacific Combat Air Transport Command, charged with establishing cargo bases.

A Politician Is Born, Midwifed by Committee

At war's end he was surprised to receive a letter from a committee of California Republicans asking if he was interested in running for Congress.

Although there had been little indication that Mr. Nixon had wanted to make politics his career, he jumped at the chance. The five-term incumbent was Jerry Voorhis, a liberal in the Truman tradition who had voted for Federal control of tidelands oil and had worked for cheap credit and for public power; the conservatives of Southern California wanted him out.

Mr. Nixon returned to California and, in competing with other candidates for the committee's endorsement, said the issues would be 'New Deal government control in regulating our lives' versus 'individual freedom and all that initiative can produce.'

'I hold with the latter viewpoint,' he said. 'I believe that returning veterans, and I have talked to many of them in the foxholes, will not be satisfied with a dole or a Government handout.' That Mr. Nixon had little opportunity for contact with servicemen in the foxholes was not important; he demonstrated a political ability to say what his audience wanted to hear. He won the committee's endorsement and the primary.

But when the campaign for the 1946 general election began, Mr. Nixon was far behind his opponent. To overcome that, he developed a technique he would use time and again: discredit your opponent.

Mr. Nixon issued a statement billing himself as a 'clean, forthright young American who fought for the defense of his country in the stinking mud and jungles of the Solomons' while his opponent 'stayed safely behind the front in Washington.'

This was coupled with another statement saying he represented no special interest or pressure group and adding, in reference to the Political Action Committee of the Congress of Industrial Organizations: 'I welcome the opposition of the PAC with its Communist principles and huge slush fund.'

Mr. Voorhis's defense, that the PAC had not endorsed him and that it was not Communist, did not deter Mr. Nixon, and when he arrived in Washington at the age of 34, Representative Nixon received a cold shoulder from some members of Congress who believed he had unseated a colleague unfairly.

The slight did not escape the notice of Mr. Nixon, who was already beginning to see himself confronted by enemies.

Fame and Alger Hiss, Politics and the Pink Lady

It was the Alger Hiss case that made Richard Nixon a national celebrity.

In August 1948, Mr. Hiss, a highly regarded former State Department official, was accused by Whittaker Chambers, a former Communist and then a senior editor at Time magazine, of having given Mr. Chambers secret Government documents for delivery to the Soviet Union in 1937 and 1938. Mr. Hiss denied the charges before the House Committee on Un-American Activities and swore he did not know 'a man named Whittaker Chambers.' Because of Mr. Hiss's excellent credentials and Government record, the matter might have been dropped had Mr. Nixon not doggedly pursued it as head of a special subcommittee.

Mr. Hiss finally acknowledged that he had known Mr. Chambers as 'George Crosley,' a freelance writer he had befriended in the 1930's. He continued to deny, however, that he had been a Communist or had passed secret documents.

After Mr. Hiss filed a libel suit against Mr. Chambers, the rumpled, rotund editor produced from a pumpkin on his Maryland farm five rolls of microfilm of documents that he said had been passed to him by Mr. Hiss. They led to Mr. Hiss's indictment on a charge of perjury, and after two trials he was convicted in 1950.

The episode was an embarrassment to Democrats who had defended Mr. Hiss. Mr. Nixon won wide praise for his persistence and astuteness in the case, but he emphasized the enemies he made.

'The Hiss case proved beyond any reasonable doubt the existence of Soviet-directed Communist subversion at the highest levels of American government,' Mr. Nixon wrote in his memoirs. 'But many who had defended Hiss simply refused to accept the overwhelming evidence of his guilt. Some turned their anger and frustration on me.'

The Hiss case made Richard Nixon famous, but it also turned him, he wrote, 'into one of the most controversial figures in Washington, bitterly opposed by the most respected and influential liberal journalists and opinion makers of the time.'

In 1950, Senator Sheridan Downey, a Democrat, unexpectedly chose to retire. Mr. Nixon, who had had his eye on the Senate seat for a couple of years, was supported by major California newspapers and was unopposed in the Republican primary. The Democrats, however, were split in a bitter primary contest in which Representative Helen Gahagan Douglas emerged the winner to face Representative Nixon.

Mrs. Douglas was a former Broadway and motion picture actress who was married to the actor Melvyn Douglas. She was a popular liberal, a Fair Dealer who had enthusiastically supported the Truman program.

From the beginning Mr. Nixon set out to discredit his opponent's loyalty to the American system. He distributed more than half a million pink fliers that said in part:

'During five years in Congress, Helen Douglas has voted 353 times exactly as has Vito Marcantonio, the notorious Communist party-line Congressman from New York. How can Helen Douglas, capable actress that she is, take up so strange a role as a foe of Communism? And why does she when she has so deservedly earned the title of 'the pink lady'?'

In fact, Mrs. Douglas was denounced by pro-Communist groups as a 'capitalist warmonger,' and it was in this campaign that Mr. Nixon was first called 'Tricky Dick,' an epithet bestowed by The Independent Review in an editorial and picked up by Mrs. Douglas in her campaign.

The extreme charges against Mrs. Douglas turned out to be overkill: Mr. Nixon won the race by 680,000 votes. But the campaign would supply Democrats with anti-Nixon ammunition for years to come.

NATIONAL SCENE

A Young Man And a War Hero: A G.O.P Ticket With Balance

It seemed strange to some that Dwight Eisenhower, a war hero running for President as a moderate, picked Richard Nixon as his running mate in 1952. But politically it made sense.

Eisenhower was reputed within the party to be the candidate of the 'Eastern liberal establishment.' He needed someone from the West or Middle West who could appeal to disappointed conservatives.

Further, the retired general knew, as Mr. Nixon later wrote, 'that to maintain his above-the-battle position he needed a running mate who was willing to engage in all-out combat and who was good at it.'

And in many ways Mr. Nixon himself projected a moderate image as a spokesman against corruption in government. At 39, he was young, bright and an effective speaker.

He first caught the attention of Eisenhower supporters in addressing a Republican dinner in New York three months before the nominating convention. Former Gov. Thomas E. Dewey of New York, twice the party's Presidential nominee and Eisenhower's chief backer, was reported to have told Mr. Nixon after his speech: 'Make me a promise. Don't get fat, don't lose your zeal, and you can be President some day.'

A Speech About Checkers, A Spot Secured

The 1952 campaign was barely under way when, on Sept. 18, a sudden crisis loomed. The New York Post and other newspapers disclosed that 78 wealthy California businessmen had quietly raised a fund of $18,235 to defray political expenses for Senator Nixon.

Although establishment of such a fund would later seem mild, the news at the time stunned much of the country. Many Democrats and some Republicans, including Eisenhower's closest advisers, demanded that Mr. Nixon resign from the ticket on ethical grounds.

Eisenhower himself was silent for several days, finally saying only: 'Nothing's decided. Nixon has got to be clean as a hound's tooth.' Each wanted the other to make the decision. After Mr. Nixon told the general by telephone that it was time for the head of the ticket to make a decision, the Eisenhower people were convinced that Mr. Nixon had to go. But the general gave him the opportunity to state his case on national television.

By any measure, his defense was a virtuoso performance. He maintained that he had done nothing wrong, disclosed his mortgages and other financing to show he was in fact in debt, attacked Communism and asked people to tell the Republican National Committee whether they thought he should resign.

His most moving, and best remembered, remarks were in reference to his wife and a dog named Checkers.

'Pat and I have the satisfaction that every dime that we've got is honestly ours,' he said. 'I should say this -- that Pat doesn't have a mink coat. But she does have a respectable Republican cloth coat.'

Then he said a man in Texas had given the family a cocker spaniel, 'black and white and spotted.'

'And our little girl, Tricia, the 6-year-old, named it Checkers. And you know, the kids love the dog, and I just want to say this right now, that regardless of what they do about it, we're going to keep it.'

Public response was overwhelmingly pro-Nixon. Eisenhower asked him to meet him on the campaign trail in Wheeling, W.Va. When the Nixon plane landed, the general hopped aboard.

'General, you didn't need to come out to the airport,' the surprised Mr. Nixon said.

Nixon Memoir In The

'Why not,' said the general, flashing his famous grin, 'You're my boy.'

After the Republican victory, Mr. Nixon turned out to be an active Vice President under a President who preferred to operate quietly. President Eisenhower was willing to delegate more tasks than most of his predecessors, and the energetic Mr. Nixon had a knack of keeping himself in the limelight, no manner how menial the assignment

.Probably his most important role was in foreign affairs. He visited 56 countries as a good-will envoy, but, more important, he served on the National Security Council, at the heart of policy decisions and intelligence. He was close to Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, whose policy of 'brinksmanship' fit perfectly with Mr. Nixon's idea of bold and even risky actions abroad.

Mr. Nixon's travels abroad generated far more news than most trips by Vice Presidents. Unlike most, he was not content to engage in ceremony and quiet diplomacy. He invited crowds to engage him in dialogue, however tense relations might be between their country and his.

Thus Mr. Nixon's 1958 trip in South America turned out to be one of the 'Six Crises' he would recall in his book. He managed sessions of crowd-mingling and argumentative discussion in Venezuela and Argentina with few problems. But in Peru crowds of students and others had been worked into an anti-Yankee, anti-Nixon frenzy by speakers and signs.

'Are You Afraid Of the Truth?'

When a rock thrown from a crowd in Lima grazed the Vice President's neck and hit a Secret Service agent in the teeth, Mr. Nixon shook his fist at the crowd and asked, 'Are you afraid to talk to me? Are you afraid of the truth?' He leapt onto the trunk of his car shouting: 'Cowards! Are you afraid of the truth?'

In a later confrontation someone spat in his face. 'I felt an almost uncontrollable urge to tear the face in front of me to pieces,' he wrote later. 'I at least had the satisfaction of planting a healthy kick on his shins. Nothing I did all day made me feel better.'

Such confrontations paid off in public acclaim. On his return to the United States, he was greeted by cheering crowds as a conquering hero

.And there was the celebrated 'kitchen debate' with the Soviet leader, Nikita S. Khrushchev, while Mr. Nixon was on a trip to Moscow in 1959 to open an American exhibit at a fair. In the kitchen of a model home, the two leaders engaged in a folksy dialogue on the relative merits of the capitalist and Soviet systems.

The two men stood jowl to jowl, the Soviet leader occasionally jabbing Mr. Nixon's chest for emphasis. The outcome was inconclusive, of course, but Mr. Nixon won acclaim at home for the forceful manner in which he defended the American system.

There were also attacks from his opponents. Frequent Herblock cartoons in The Washington Post showed him with a shadowy, hateful face; some showed him climbing out of a sewer to give a campaign talk. The Duke faculty voted 61 to 42 against giving Mr. Nixon an honorary degree.

Richard Nixon could never give up politics, however. He had tasted power and the excitement of living on the precipice, and he liked it. Pat Nixon, though she would still try to persuade him to retire from politics, resigned herself year after year to 'another campaign.'

AIMING HIGHER

One Ballot, Four Debates, Two Defeats, And a Recovery

After the Eisenhower-Nixon ticket won again in 1956 by a wide margin, defeating Adlai E. Stevenson for a second time, Mr. Nixon groomed himself for the 1960 Presidential nomination. A rival, Gov. Nelson A. Rockefeller of New York, abandoned his efforts after Mr. Nixon's popularity shot up in the wake of the 'kitchen debate.'

The Republicans nominated Mr. Nixon on the first ballot at their convention in Chicago. Trying to appeal to the 'Eastern establishment,' he chose Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts as his running mate. The Democratic ticket was Senator John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts and Senator Lyndon B. Johnson of Texas.

The campaign went badly from the beginning. For the first time in his career, Mr. Nixon was on the defensive, forced to defend the Eisenhower record and to erase his reputation as an unfair campaigner.

Eisenhower, who had always had trouble embracing Mr. Nixon, did not help. At a news conference he was asked for an example of a major idea of Mr. Nixon's that had been adopted by the Administration. 'If you give me a week, I might think of one,' he replied. 'I don't remember.'

And the Nixon campaign itself was in many ways uncharacteristic. Mr. Nixon, who had always seemed prepared to take on any opponent anywhere, held Senator Kennedy and his family in awe in a way few of his supporters could understand. He admired the Kennedy family's fighting spirit and their wealth and status. Whatever the reason, he broke from his practice, and never made a slashing attack on his opponent..

A noted debater, he was not at his best in the four television debates with Mr. Kennedy. He was tense, and he declined the use of makeup: his dark beard and pasty forehead, with beads of sweat, made him appear on television to be the shadowy figure that cartoonists had depicted.

Throughout the campaign, the Vice President's serious, sometimes prim, demeanor was overshadowed by the charisma of the young Senator. This seemed more important than questions about an interest-free $205,000 loan from Howard Hughes to Mr. Nixon's brother Donald or such issuesas which candidate would be toughest against the Russians and which could, in Mr. Kennedy's words, 'get this country moving again' in the wake of a recession.

A Quiet Pledge: 'I Would Be Back'

Still, Mr. Nixon campaigned as doggedly as he ever had, and the outcome was extraordinarily close. In the popular vote Mr. Kennedy led by 113,000 out of 68.8 million cast. It was Mr. Nixon's first defeat and the last he would accept graciously. Many Republicans, believing that Democratic machines in Chicago and Texas had stolen the election for Mr. Kennedy, wanted to contest the outcome. But Mr. Nixon would not.

In his memoirs, he wrote that on the night of Mr. Kennedy's inauguration, when happy Democrats were celebrating throughout Washington, he went alone to the deserted Capitol and stood for several minutes on a balcony overlooking the snow-covered Mall and the Washington Monument. 'As I turned to go inside, I suddenly stopped short, struck by the thought that this was not the end, that someday I would be back here. I walked as fast as I could back to the car.'

At the age of 48, Mr. Nixon returned to California and entered the 1962 race for Governor against the incumbent, Pat Brown, a Democrat seeking a second term.

It was another tumultuous campaign of charges and countercharges, but in the end the voters seemed to recognize what Mr. Nixon admitted in his memoirs: he did not really want to be Governor; he wanted to be President.

The night of his defeat he was in a foul mood. Mr. Nixon felt he had been abused by the press, and when reporters kept insisting that he make a statement, he marched into the press room and made an angry farewell-to-politics speech that included the line, 'You won't have Nixon to kick around anymore, because, gentlemen, this is my last press conference.'

Almost everyone believed that his political career was over. He had violated a basic rule of American politics: Never appear to be a poor loser.

But after that night he began a slow, measured recovery that would lead to victory in two Presidential elections. He wrote in his memoirs:

'I have never regretted what I said in 'the last press conference.' I believe that it gave the media a warning that I would not sit back and take whatever biased coverage was dished out to me. I think the episode was partially responsible for the much fairer treatment I received from the press during the next few years. From that point of view alone, it was worth it.'

Ever restless, he moved to New York as a senior partner in a Wall Street law firm whose name became Nixon, Rose, Guthrie, Anderson & amp; Mitchell. The Nixons settled in an expensive apartment on Fifth Avenue.

But Mr. Nixon spent little time as a lawyer. Rather, he worked at becoming President. The crushing defeat of its 1964 nominee, Barry Goldwater, left the Republican Party in a shambles. And it was Mr. Nixon who moved in and did the drudge work needed to rebuild a constituency, attending the dinners, the rallies, the conventions.

In 1966 he chartered a sputtering DC-3 to take him around the country to speeches on behalf of Republican Congressional candidates. Although his plane was modest, Mr. Nixon managed to appear Presidential, the head of a party that was starting to capitalize on the weaknesses of the Johnson Administration as public opposition to the Vietnam War mounted and as many people became fearful of rising crime and civil disorder.

On Jan. 31, 1968, he formally announced his candidacy for the Presidency. He rolled easily through the primaries. With the help of Southern conservatives, attracted by a promise that he would ease off on school desegregation, he won the nomination at the party's convention in Miami Beach on the first ballot, defeating Governor Rockefeller of New York, a liberal, and Governor Reagan of California, a conservative.

As in the 1950 Senate race, the cards fell Mr. Nixon's way. President Johnson withdrew as a candidate for re-election because of the opposition to the Vietnam War. Senator Robert F. Kennedy was assassinated in Los Angeles in June while campaigning for the Democratic nomination. Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey was nominated over an antiwar candidate, Senator Eugene J. McCarthy of Minnesota, at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago while the police and demonstrators fought in the streets. But Mr. Humphrey was too closely tied to Mr. Johnson's policies for many Democrats, and when he finally announced his independent opposition to the war, it was too late to heal the wounds.

Millions of independents and moderates in both parties saw Mr. Nixon as a suitable alternative to another Democratic administration. At the age of 55 he seemed to have put the excesses of his youth behind him. His mastery of foreign affairs and the prospects that he would bring an era of reforms after years of hastily enacted 'Great Society' programs at home appealed to many.

And in 1968 he was able to control as never before the image he projected to voters. By then, candidates could be and were packaged and sold on television. Campaign tours and rallies were useful mostly for showing on TV screens. The reality of a campaign could be altered to project the desired image.

John D. Ehrlichman, later a top White House assistant, recalled the campaign in his book, 'Witness to Power.' At an Oct. 31 rally in Madison Square Garden, for example, Nixon supporters were bused in from distant suburbs to fill the hall, while those off the street who looked as if they might boo or heckle the candidate were directed down a corridor that led back to the street.

'The television audience,' Mr. Ehrlichman wrote, 'saw only the thunderous cheering of a friendly, enthusiastic crowd of enlightened American voters.'

Mr. Nixon won the popular vote by a narrow margin and got 301 electoral votes to 191 for Mr. Humphrey and 46 for Gov. George C. Wallace of Alabama, on a third-party ticket.

FIRST TERM

More Spending, More Control, More Justices, More War

When Mr. Nixon became President, he had never before wielded executive authority. But he had been around power for so long and went to such great pains to keep abreast of affairs at home and abroad that he knew exactly what he would do.

Much of what he did in the domestic area was aimed at cementing his re-election in 1972, several Nixon aides said. He began by appointing a broadly based Cabinet that included elected officials like Gov. George Romney of Michigan as Secretary of Housing and Urban Development and Walter J. Hickel, the former Governor of Alaska, as Interior Secretary. He named Daniel Patrick Moynihan of New York, who had been a liberal in the Kennedy Administration, as his chief urban affairs adviser, and Henry Kissinger, an adviser to Governor Rockefeller, as his chief foreign policy aide.

Despite his promises during the campaign and his Presidency to trim Government spending, Mr. Nixon presided over an expansion in spending. One reason was that he had to deal with a liberal, Democratic Congress. Another was that he did believe in many innovations for Government aid, and in the 1970's there was a strong public demand for such services.

He proposed a family assistance program that would have been more generous than the traditional welfare then on the books, he backed safety and health protection for workers and he called for housing allowances that would have moved many families out of public housing by giving them money to rent their own. His Administration built more subsidized housing units than any before or since, and he agreed to environmental legislation, including the Environmental Protection Act, that would pour billions into cleaning up the nation's air and waters.

Although few noticed it at the time, Mr. Nixon's expansion of the food stamp program would later be acknowledged as a remarkable breakthrough in social policy by a President who preached austerity: by 1982 it was helping to feed 1 in 10 Americans.

Another innovation that had an important effect on the nation was the program under which the Federal Government took several billion dollars each year from its tax receipts and distributed it, with few strings attached, to local governments. Looking to re-election, Mr. Nixon opted to give local officials the maximum authority over use of these revenue-sharing funds.

A 1972 Strategy To Comfort the South

But much of this was little noticed at the time because of some of Mr. Nixon's positions on civil rights and his efforts to win the support of Southern conservatives breaking away from the Democratic Party.

He backed off on enforcement of school desegregation, supporting legislation and executive action that would vastly reduce the use of busing as the chief tool in achieving integration.

A cornerstone of this 'Southern strategy' was his effort to change the makeup of the Supreme Court. Two conservative nominees from the South were rejected by the Senate, but Mr. Nixon was still able to reshape the court with four appointments: Warren E. Burger as Chief Justice, and Associate Justices Harry A. Blackmun, Lewis F. Powell Jr. and William H. Rehnquist. In much of his Presidency, Mr. Nixon faced a troubled economy, and as pressure from Congress and the public mounted for him to do something to check inflation, he imposed wage and price controls in mid-1971.

The controls required him to set up the kind of bureaucracy he had hated in World War II. And when they were lifted, after the 1972 election, prices shot up again.

'What did America reap from its brief fling with economic controls?' Mr. Nixon asked in his memoirs. 'The Aug. 15, 1971, decision to impose them was politically necessary and immensely popular in the short run. But in the long run I believe that it was wrong. The piper must be paid, and there was an unquestionably high price for tampering with the orthodox economic mechanisms.'

| Author | Richard M. Nixon |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Memoir |

| Publisher | Doubleday |

Publication date | 1962 |

| Media type | Hardback |

| ISBN | 9780671706197 |

| Followed by | RN: The Memoirs of Richard Nixon |

Six Crises is the first book written by Richard Nixon, who later became the 37thpresident of the United States. It was published in 1962, and it recounts his role in six major political situations. Nixon wrote the book in response to John F. Kennedy's Pulitzer Prize–winning Profiles in Courage, which had greatly improved Kennedy's public image.[1][2][3]

Background and writing[edit]

Six Crises was Nixon's response to the John F. Kennedy book, Profiles in Courage (1955), which described the courage of eight US Senators.[2][3] Kennedy sent Nixon a copy of his book, for which Nixon thanked him the next day.[1] In 1961, following his 1960 presidential defeat to Kennedy, Nixon was encouraged by Mamie Eisenhower to write a book about his experiences. On April 20, he visited Kennedy in the White House where Kennedy urged him to write a book; he said that doing so would raise the public image of any public man. Nixon met with a Doubleday book editor the same month.[4]

Like Kennedy, Nixon used a ghostwriter for much of his book. The primary such writer was reportedly Charles Lichenstein.[5] Years later, Nixon's editor at Doubleday, Kenneth McCormick, recounted: 'I enjoyed working with him on 'Six Crises.' He had the concept for the book. He had the whole thing in his head, but he said, 'I'm not much of a writer,' and I said, 'I know.' So Nixon talked the book into a tape recorder and another writer came in to help. Then Nixon said, 'Why don't I try the chapter on defeat? In the course of doing this I think I've learned to write.' Well, he wrote that chapter himself, and it was fine. He really was an example of someone who could learn.'[6]

Contents[edit]

The book is organized around the titular six stressful circumstances.

Alger Hiss case[edit]

In 1948, Nixon was a member of the United States House of Representatives serving on the House Un-American Activities Committee, which was investigating communism in the United States. He first rose to national prominence when the committee considered accusations that Alger Hiss, a high-ranking United States Department of State official, was a communist spy for the Soviet Union, allegations that remain a source of controversy.

Fund crisis and Checkers speech[edit]

In 1952, as a member of the United States Senate, Nixon was the vice presidential running mate of Republican presidential nominee Dwight Eisenhower. After he was accused during the campaign of having an improper political fund, he saved his political career and his spot on Eisenhower's ticket by making a nationally broadcast speech, commonly known as the Checkers speech. In the speech, he denied the charges and famously stated he would not be giving back one gift his family had received: a little dog named Checkers.

Eisenhower's heart attack[edit]

In 1955, while Nixon was vice president, President Eisenhower suffered a serious heart attack; during the next several weeks, Nixon was effectively an informal 'acting president'.

Attack by a mob in Venezuela[edit]

In 1958, Nixon and his wife embarked on a goodwill tour of South America; while in Venezuela, their limousine was attacked by a pipe-wielding mob.

Kitchen debate in Moscow[edit]

In 1959, while still vice president, Nixon traveled to Moscow to engage in an impromptu debate with Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev. The debate took place in a mock kitchen that was intended to show Soviet citizens how ordinary American families lived, and came to be known as the Kitchen Debate.

Loss in 1960 presidential campaign[edit]

While finishing his second term as vice president, Nixon became the Republican presidential nominee; in the 1960 United States presidential election, he lost an extremely close race to Senator John F. Kennedy.

Commercial performance[edit]

Six Crises was a best seller at the time.[7] Sales were of over 300,000 copies and it was excerpted at length in LIFE magazine.[8]

References[edit]

- ^ abMatthews, Christopher (1997). Kennedy & Nixon: the rivalry that shaped postwar America. Simon and Schuster. p. 106. ISBN0-684-83246-1.CS1 maint: discouraged parameter (link)

- ^ abDelson, Rudolph (November 10, 2009). 'Literary Vices, with Rudolph Delson: Richard Nixon's 'Six Crises''. The Awl. Archived from the original on February 27, 2011. Retrieved February 22, 2011.CS1 maint: discouraged parameter (link)

- ^ abRoper, Jon (1998). 'Richard Nixon's Political Hinterland: The Shadows of JFK and Charles de Gaulle'. Presidential Studies Quarterly. Retrieved February 22, 2011.CS1 maint: discouraged parameter (link)

- ^Nixon (1962) Introduction to Six Crises.

- ^[https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/national/longterm/watergate/stories/nixon17.htm 'Behind the Statesman, A Reel Nixon Endures', Washington Post, June 17, 1997.

- ^'Publishing's Kenneth McCormick, 91, Dies', New York Times, June 29, 1997.

- ^[https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/jul/19/richard-nixon-book-memoirs-watergate-1989 'Richard Nixon plans 'most personal book ever'], The Guardian, July 19, 1989.

- ^Jonathan Aiken, Nixon: A Life, p. 348.